- Unbreaking The News

- Work

- Life

- Lifestyle

- HumanityDiscover the latest trends, style tips, and fashion news from around the world. From runway highlights to everyday looks, explore everything you need to stay stylish and on-trend.

- Mental HealthStay informed about health and wellness with expert advice, fitness tips, and the latest medical breakthroughs. Your guide to a healthier and happier life.

- Science & Technology

- Literature

- About Us

- Unbreaking The News

- Work

- Life

- Lifestyle

- HumanityDiscover the latest trends, style tips, and fashion news from around the world. From runway highlights to everyday looks, explore everything you need to stay stylish and on-trend.

- Mental HealthStay informed about health and wellness with expert advice, fitness tips, and the latest medical breakthroughs. Your guide to a healthier and happier life.

- Science & Technology

- Literature

- About Us

Now Reading: Shifting Fortunes, Shifting Fates

-

01

Shifting Fortunes, Shifting Fates

- Unbreaking The News

- Work

- Life

- Lifestyle

- HumanityDiscover the latest trends, style tips, and fashion news from around the world. From runway highlights to everyday looks, explore everything you need to stay stylish and on-trend.

- Mental HealthStay informed about health and wellness with expert advice, fitness tips, and the latest medical breakthroughs. Your guide to a healthier and happier life.

- Science & Technology

- Literature

- About Us

Shifting Fortunes, Shifting Fates

I still remember the night my father died. The years before were a blur of lavish parties with older men shrunken with age and tall bottles of wine and beer. They visited often, these rich men with their families.

Sundays saw my mum and Aunty Nneka, barely a teenager herself, in the kitchen pounding soft yams in our large brown mortar until the ground shook. Laughter could be heard for many hours. They spoke boisterously in loud voices over peppered chicken that made their noses run. It felt like the excitement would never end. Until it did.

I am five

We were a typical Nigerian family. My father attended the men’s meeting and the community meeting, and he donated rather too generously to the church. My mum would tug on his white kaftan as he called out hefty sums like five hundred thousand naira or when he volunteered to finish the church building single handedly. He walked with a poise that oozed pride. His gait was daunting and my mum complemented his look, sitting beside him in a pretty embroidery that radiated affluence. Her headscarf did not make crunchy sounds like the biscuit-like wraps worn by other women in the church. Her gold did not tarnish, nor did her lipstick wane. Her skin was as radiant as day, fresh from the beauty products my father bought her. I ran around the church in my pearly white gown and ponytails, and Aunty Nneka chased me, pulling me by one hand and dusting off my dress when I fell on dirt.

Everyone clustered about our Peugeot after mass and greeted my father, but even as a child, I knew most of their overcompensating pleasantries were borne out of their desire to ask for money. Many carried me high on their shoulders. I was five, but I remember it all. They said I was turning into such a lovely and plump child even though I was scrawny, for my age. My father would dip his long fingers with perfectly manicured nails into his pocket and pull out a wad of crisp notes, giving it to them. He dropped two hundred naira onto the enamel plates held by people begging by the church’s gate when others dropped torn ten naira notes.

(Image courtesy of Adi Goldstein via Unsplash)

I am six

My sixth birthday was bright and festive with balloons floating in the air and children running about our compound. I stepped on my gown and the lacy extension got torn. My mom scolded me by tugging my ear, so my dad reprimanded her.

As usual, he was clinging tightly to his phone and would hurriedly pick it up at the first ring. Mum was pregnant with my little sister then, and since she was a full-time housewife, she worried over things that ordinarily should not be a concern like when Aunty Nneka put the stew in the yellow bowl instead of the white one. They were both large enough but with my mum, details mattered. No one worried that her nagging was becoming unbearable because she was pregnant. She alone knew, however, that it was not the pregnancy that made her so quick to anger. My father had been cheating on her.

***

He is coughing

Our lives changed a few months after the birth of Chidinma, my baby sister. My father fell ill. He coughed more often and ate less. He shrunk, looking shriveled on the bed. My mother worried about him even more when the hospital could not figure out what ailed him.

The parties became few and far between. Friends rarely visited. My mother dug into the last of my father’s savings and discovered, rather later, that we had fewer assets and more liabilities. We were drowning in poverty as she pumped money into different hospitals, hoping he would get better. He did not.

Aunty Odinaka called rather abruptly on an early Sunday morning. My mother sat with a drooping breast stuck into Chidinma’s ready pink lips. She had stayed up all night to attend to my father, who had remained motionless on his back, struggling to breathe. Aunty Odinaka was my father’s younger sister who had lived with us when she was a student. She referred my mum to a spiritualist in the village, and for what seemed like several hours, my mum refused.

“Ekwu Zina, don’t say that,” she said over and over. She pointed out how diabolical and fetishistic the practices were, how the bible was strongly against them, and how she could never take my father there.

She changed her mind, however, when my father deteriorated to the point that he stopped moving. My mum tried reaching out to Alhaji Muhammed, my father’s best friend and business partner, who had a round belly and white stubble across his chin. He had given her an envelope heavy with cash, greedily consumed by the hospital in a single day. When my mother called him again, he cut off all communication with us. Even I, now grown and fully able to grasp the gravity of always asking for help, understood why he did that.

My mother was flustered. The very people she threw lavish parties for now ignored her calls. At first, our house still looked the same with the central gold table and a low chandelier that glowed gently with warmth. It burned my eyes when I stared for too long and the tiny bulbs hung like mango fruit. Then in a few weeks, the golden center table had been sold, and the family car and everything that smelled of luxury had been removed.

I watched butter leave the table as my mum told me that it tasted sour so she stopped buying it.

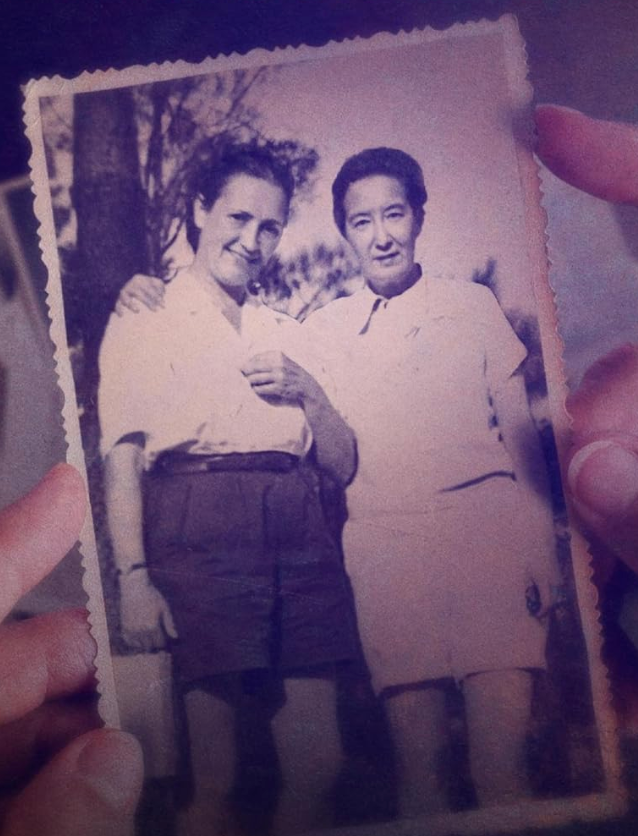

(Image courtesy of Ravi Kant via Pexels)

Later, she would stop buying my favorite treats: Sugary Capri-Sonne drinks were no longer at our usual shops, she explained. I had stopped going to school, because she was no longer satisfied, it seemed, with the teachers.

***

I am present

The spiritualist was a short man with white material wrapped over his shoulder and under his arm. He often had a leaf frond between his lips and hummed on it fervently. I came to watch the healing magic at the spiritualist’s request: he said that I was a major connection to my ailing dad and must be present.

I stared in disbelief as I watched him pace about the lanky remains of my father and dunk him into the shallow river. He picked up a gourd from a calabash — its edges so poorly cleaned that tiny bits of wood stuck out — and he ran it over father’s face three times.

After an hour passed and we were sure that no magic was going to happen, we asked the spiritualist what the matter was. His eyes burned a painful red, the kind gotten from downing tall bottles of alcohol, as he urged us to be patient. He proceeded to apply a mild cream over my father’s body and towed him back to the car.

Fear enveloped us all when my mother felt his face. She could no longer feel the warm breath from his slender nostrils. Only our shifting fates.

(Image courtesy of Godiva Omoruyi via Pexels)

Chiamaka

Chiamaka Jennifer Asadu is a graduate of Pharmacy, from the prestigious University of Nigeria, Nsukka. She is a proficient writer and an avid reader. Having volunteered both online and offline for non-governmental organizations, she has honed her skills in communications and human interaction over the years.

Thank you to Yosef Baskin and Molly Corso for their inspired edits on the piece.

Related Posts

Editorial10 months ago

Almost Lost Forever: True Love and Survival

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

Business3 days ago

Cadence: I Got Rhythm