- Unbreaking The News

- Work

- Life

- Lifestyle

- HumanityDiscover the latest trends, style tips, and fashion news from around the world. From runway highlights to everyday looks, explore everything you need to stay stylish and on-trend.

- Mental HealthStay informed about health and wellness with expert advice, fitness tips, and the latest medical breakthroughs. Your guide to a healthier and happier life.

- Science & Technology

- Literature

- About Us

- Unbreaking The News

- Work

- Life

- Lifestyle

- HumanityDiscover the latest trends, style tips, and fashion news from around the world. From runway highlights to everyday looks, explore everything you need to stay stylish and on-trend.

- Mental HealthStay informed about health and wellness with expert advice, fitness tips, and the latest medical breakthroughs. Your guide to a healthier and happier life.

- Science & Technology

- Literature

- About Us

Now Reading: Me: The Kenyan Father, and the British Father

-

01

Me: The Kenyan Father, and the British Father

- Unbreaking The News

- Work

- Life

- Lifestyle

- HumanityDiscover the latest trends, style tips, and fashion news from around the world. From runway highlights to everyday looks, explore everything you need to stay stylish and on-trend.

- Mental HealthStay informed about health and wellness with expert advice, fitness tips, and the latest medical breakthroughs. Your guide to a healthier and happier life.

- Science & Technology

- Literature

- About Us

Me: The Kenyan Father, and the British Father

Dreams of opportunity

“I finally get out of this frustrating country and explore!’’

It’s not that I lack patriotism for my country, but honestly, that is how I felt when I finally secured my visa to the United Kingdom. What could be more exciting for someone like me from a “Third World” country like Kenya than securing an opportunity to live and work among the citizens of Great Britain?

My destination? Oxfordshire, a far cry from Nairobi City, the alleged capital of Africa. I am heading to a whole new world of hope.

Migrating to the UK was like a golden opportunity for my family and me, and for my daughter specifically, since I believed she would be able to get a top-tier education, better social amenities, and, of course, get to interact with a different cultural community. At least, that is what I thought. Little did I know that all that awaited me was but exhaustion and stress from relocating and missing my family, my friends, and the warm tropical weather back home. In fact, by the time I landed in the UK, I immediately found myself appreciating the climate and weather back home in Nairobi.

Migrating from expectation to exhaustion

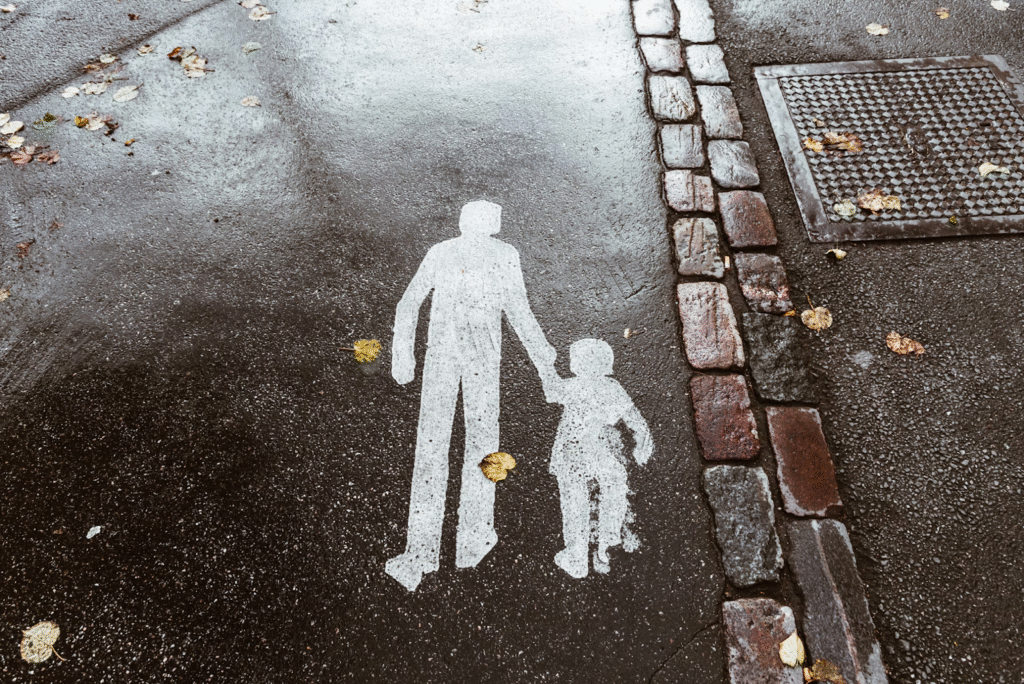

I convinced myself that it was just a matter of time before I’d get used to this cold weather. At least this seemed to be the least of my problems. But in reality, things were difficult, more so since I was an immigrant and I was not used to life here. I was navigating an unfamiliar environment. I had to look for a school for my young daughter, get a mortgage, and, of course, settle into my new job. It was at this point that it hit me — I now had a caretaking role to fulfill.

I got my daughter into a primary school, but here, things were very different. For instance, once you enroll your child in a school in Kenya, they become the responsibility of the school; you are not obligated to pick up your child from school because the school bus would drop them right at their estate. Then, typically, the maid would go and pick them up if the drop-off point happened to be far from your house. If the school is in a rural setting or the child is old enough, they are free to walk back home without fear of jeopardy, since even strangers can act as carers. But here in the UK, it was a different story.

First of all, the language barrier was a heavy stone to roll, especially for my daughter, who was used to a creole of Swahili and English. However, in the UK, there was only English with a strong British accent. It was a challenge for her. Then, the environment was like a monster to her. Often, she would catch flu due to the cold climate here – unlike in Kenya, where the warm climate is easier on the immune system.

The pressure of caregiving started weighing on my shoulders. I was the primary caregiver here. You see, a benefit to living in Kenya is that there was a network (family, friends, neighbors) who helped hold everything together. But here I was alone with just my immediate family. We lacked other support to lean on.

Back to my daughter and her school routine. Daily, I had to wake up at 6:00 a.m. to get sorted for work and at the same time prepare my daughter for school, as she was supposed to report to school at 8:30 a.m. Furthermore, I had to make sure that her breakfast was ready before 7:00 a.m. and also pack her lunch, all before I even thought about my own day.

Back in Kenya, this was never a problem, as her nanny took care of this. But here in the UK, hiring a nanny is very expensive. Because children cannot be left alone, everything was for her mother and me to do.

As if that was not enough, I also had to pick her up from school. School ends at 3:15 p.m., which is an hour and forty-five minutes early, given that my work day ends at 5 p.m. There are school clubs, but there is a fee to participate. If you want to coordinate home drop-off with the school, it is double the price of picking her up by yourself.

My caregiving role does not end here. After school is the most exhausting part. When we get home, I have to help her with her homework and any projects she may have. All this I do, and at the same time, I have to keep up with my job. The school encourages registering children for weekend clubs, and this, too, requires a parent’s presence and extra expense.

Other school-related tasks include: being up to date with school news, attending the parent-teacher meetings, talent shows, and exhibitions that are sometimes scheduled on workdays. In order to accommodate all of these activities, I have to build them into my work schedule. With school trips, I have to plan properly so that she can also enjoy herself as the other students do, and not feel left out. At times, I felt overwhelmed by these responsibilities, and wished I could return home. Seriously, why did no one tell me about what’s involved in transitioning from the Kenyan school system to the UK one?

Transition and growth

Eventually, with repetition, my daughter and I adjusted to her new schedule and academic requirements and soon, some of the responsibilities, like picking her up from school, were reduced because she could come home by herself. The parenting culture clash I experienced was not just about changing and securing greener pastures and a better living environment for my family, especially for an immigrant. It entailed much more than that. This process taught me how to be present for my family and what kind of a caregiver, teacher, cultural guide, and loving parent a school-age child needs.

Living in a foreign environment, I felt like every interaction and activity that contributed to my adaptation to the new culture robbed me of my strength emotionally, physically, and mentally. I was confronted with customs that nobody ever told me about. In my role as a parent, I felt like my burnout was an endless tunnel and that I would never see the light. But gradually, I learned to work my way through it until I finally reached the other side.

Indeed, sometimes, to survive, you just have to be present, even when everything around you feels overwhelming.

Fredrick Odongo

Fredrick Odongo is a father, writer, tutorial fellow, and researcher. He writes on areas of biological and physical sciences, lifestyle, and psychology. He is currently exploring several nonfiction and fiction pieces on mental health.

Thank you to Tripti Mund & Emily Delnick for their inspired edits on the piece.

Related Posts

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

Editorial2 days ago

The Doors of Misconception

Humanity5 days ago

The Day A Stranger Saved Me