Almost Lost Forever: True Love and Survival

When the extraordinary Swedish documentary “Nelly & Nadine,” directed by Magnus Gertten, was released in 2022, it was featured in over 100 festivals and received more than 20 international awards, mainly in Europe. Thankfully in the US, it is now widely available on streaming services like Amazon Prime. For me, it was one of those films that stays with you, makes you think, makes you remember, makes you well up with tears.

“Nelly & Nadine” is a true story about two women who became lovers at the most harrowing place and time — a concentration camp during WWII. Somehow, they survived. If it weren’t for a benevolent granddaughter named Sylvie, their story would have been lost.

This documentary spoke to the heart of my own struggles and experiences as a lesbian of Jewish heritage. As a child, I knew my family’s immigrant story, how they crammed onto ships headed to America from Eastern Europe in the early 20th century. Those who stayed behind never visited us, and their lives passed from view.

I was over sixty when I first visited Prague and went to the historic Jewish cemetery. Written on a memorial wall were the family names of Jews who were transported and killed at the Terezin concentration camp. My eyes scrolled down the lengthy list and stopped short at one name: Rappaport, the family name of my mother’s father. I gasped as a chill went down my spine. If I hadn’t gone to that old graveyard, their fate would have been lost to me.

Delving into their story

The story of “Nelly & Nadine” begins at a remote farmhouse in Northern France.

The elderly Sylvie Bianchi goes to the attic and opens dusty boxes, which contain her dead grandmother’s diary, letters, photographs, and home movies. She and her husband became the custodian of the boxes after her mother’s death. They faithfully kept them for many decades, as Sylvie had fond memories of her grandmother, Nelly Mousset-Vos (1906-1987), who had been an opera mezzo soprano of considerable talent.

Nelly

All Sylvie knew of Nelly was the kind, gray-haired woman with the wonderful voice who came to spend Christmas holidays with her French family, traveling all the way from her home in Caracas, Venezuela. After the end of WWII, Nelly moved there with a woman named Nadine. Sylvie knew only that Nadine was just her grandmother’s friend and housemate. Their relationship was still a secret.

Sylvie was curious and at some point in her search, she found Nelly’s diary. She read only a few lines before it was too painful to continue. Her grandmother never spoke to any family member about her two years in various Nazi concentration camps, but there it was all laid out in words. Finally, she dared to go further, and what she found was astounding.

Sylvie decided to share Nelly’s archive, so this documentary could be made. Researchers, historical recordkeepers, and friends of Nelly and Nadine helped to flesh out their true story. As the story was unearthed bit by bit, Sylvie participated in the key interviews and was shown the documents. She came to appreciate her grandmother not only as a remarkable person, but also as a hero of France.

Sylvie knew that Nelly performed in cities all over EuropeIn the 1930s, and that she had two children (her marriage ended in divorce.) She learned that after the Nazi occupation of France in 1940, her grandmother joined the Resistance as part of a spy ring. In 1943, Nelly was swept up and arrested by the Gestapo in Paris and sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. The prisoners were forced to do hard labor under terrible conditions; if they couldn’t work, they were killed.

Nadine

Old photographs and home movies revealed what the mysterious Nadine looked like. She had a tall, elegant figure with short dark hair and often dressed in trousers, a shirt, and tie. Born in Madrid, Nadine Hwang (1902-1972) was the daughter of a high-ranking Chinese diplomat and a Belgian mother. She was educated in multiple languages.

Nadine moved to Paris in 1933 and became part of the feminist/lesbian circle around Natalie Barney (1876-1972). A playwright, poet and novelist, Barney hosted a salon of notable artists and writers at her Left Bank home. Nadine became Barney’s chauffeur and one of her casual lovers. Nelly’s memoir stated that Nadine helped at-risk people escape from occupied France to Spain, which led to her arrest and transportation to Ravensbrück in May 1944.

Nelly and Nadine

By Christmas Eve 1944, Nelly was forced to perform carols. Nadine called out a request.

With Nelly and Nadine meeting in the camp, their relationship became intimate and passionate. Against all odds, their love for each other kept them alive. They were separated when Nelly was later transported to the notorious Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Forced labor in the stone quarry usually meant death, and Nelly was close to the edge at this camp. Her intense memories of Nadine kept her going. As it happened, this was late in the war.

The film shows a poignant clip of a movie taken in 1945 when a group of liberated prisoners from Ravensbrück arrived in Sweden. You see the faces of the survivors deliriously happy to be alive and start their recovery. Nadine was in that crowd. Hers was the only sad, tense face. At the time, no one understood the reason. Nadine was thinking of Nelly. Was she alive or dead?

By some miracle, Nelly had survived, and they found each other again.

The real reel — my own story

What followed after the war was the story of so many gay men and women before the gay liberation movement of the 1970s.

I know because I was around then.

In 1965, I was a sophomore at UC Berkeley when I phoned my father from the dorm. I told him that I wasn’t returning home for the summer. I’d met someone I wanted to be with, someone I loved. Her name was Caitlin. My father exploded, calling me a child, an infatuated fool. He told me to come home or all financial support would end.

I went with Caitlin, and my life became one of desperate struggle to stay in school and graduate. But I did.

The price of being honest and true to oneself was so high that gay people had to make heartrending decisions. Some had secret lovers under the beard of a straight spouse. To keep a career and paycheck, one’s real private life was never spoken about at work. Coming out meant stiff societal consequences (even criminal in the case of men). On the streets, fluid gender or flamboyant clothes raised the risk of being beaten or killed.

Not to compare to the camps, but no gay abandon for society’s rejects, either. Despite the passage of marriage equality and wider acceptance, it’s still tough out there for so many.

Buenos Dios, Caracas

Nelly and Nadine were likewise determined to live free and honest lives. Staying in Europe was too painful after what they experienced in the camps and too close to Nelly’s family.

(Photo courtesy of Egildes Rivero via Unsplash)

They picked Caracas, Venezuela — sunny and inexpensive with available jobs for educated, multilingual Europeans. The home movies showed them relaxing and entertaining their queer friends. They lived as partners until Nadine died in 1972.

Especially moving was the way Nadine filmed Nelly at their Caracas apartment. She caught Nelly deep in her own thoughts. Her face reflected a profound inner sadness, as her time in the camps could never be forgotten. One can only imagine that those memories were crushing and tragic.

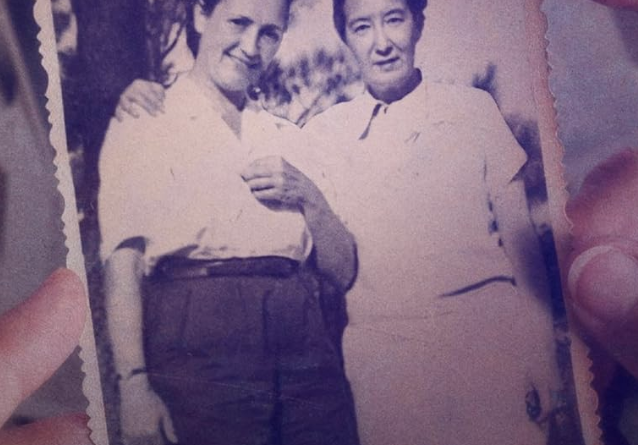

(Photo courtesy of Frameline48)

But she had Nadine, and they endured those memories together, always together. Love is love, that’s all, and that’s enough.

Emily L Quint Freeman

Emily L Quint Freeman is the author of the memoir “Failure to Appear, Resistance, Identity and Loss” (Blue Beacon Books). Freeman also wrote non-fiction articles appearing in digital magazines including Salon, Narratively, Drizzle Review, Creation, The Mindful Word, GO, The Gay & Lesbian Review, Mocking Owl Roost, and Open Democracy.

Thank you to Yosef Baskin, Julianna Wages, and the Lifestyle team for their inspired edits on this piece.