(Audio recording by Laura Rodríguez-Davis)

When thinking about services for refugees and displaced people, we often consider food, clothing, shelter, and medical aid. Rarely do we think about play. Yet, “Play is essential for children’s development,” says Rachel Sykes, director of Project Play. Even children caught in the throes of migration need the opportunity to play — something that Project Play provides.

A grassroots NGO based in northern France a short hop across the sea from Britain, Project Play offers displaced children the chance to participate in one of the most fundamental aspects of childhood: playing. As Sykes describes, “Many of the children we work with have not had access to formal education for some time, and they may also be experiencing toxic stress due to the conditions they live in. Our sessions hope to offer them a safe space in which they can relax, develop skills and feel a sense of autonomy.”

When founders Claire and Cole first came to the migrant camps at Dunkirk as students in 2018, they were helping with food distribution for the community near the French border. However, they noticed that the children, often disruptive, were simply bored, needing enrichment and engagement. In response, Cole shaved their own head to raise money, and they and Claire dropped out of university to found Project Play.

Play is serious business

So, why play? When Project Play first began, it attempted to focus on both play and formal education, but quickly realized the difficulty of trying to provide education to children, many of whom had never had formal education, in the midst of a crisis. After consulting with psychologists, they decided to narrow their focus to play only as a means of developing important skills such as, “…fine and gross motor skills… exploring the world around them, health and self-care, listening and concentration, being creative, emotional awareness and regulation, participation and collaboration and self-confidence and self-esteem,” Sykes informs.

Play can also provide a meaningful avenue for processing trauma, a common experience of children in the middle of being displaced from their homes. Furthermore, play lets kids develop social skills and make positive memories, especially important in the face of such hardship.

Go, Team Go!

Five years on from its launch, Project Play continues to provide support to displaced children in Calais and Dunkirk through the power of play. They have collaborated with child psychologists and a network of professionals to bring meaningful sessions of play to migrant youth at the French border. Their team has grown to include a board of trustees and volunteers.

Volunteers contribute to sessions, bringing their interests and talents to the table. “We have the most amazing team of volunteers who have come up with some truly engaging ideas,” Sykes enthuses. “Puppet theaters, giant xylophones, treasure hunts and a dragon’s cave have all featured!”

Understanding how valuable volunteers are to this work, Project Play also prioritizes the care of its volunteers, offering accommodation, nutritious meals, and access to mental health services. “Some team members may have a check-in or a call with a mental health professional as we have different avenues for volunteers to look after their wellbeing,” Sykes states.

Additionally, volunteers are offered opportunities for their own development. Project Play provides “really high-quality training carefully designed so that they can have a good understanding of the context, our work and the risks alongside skilling them up to be effective playworkers,” Sykes expresses. They are also encouraged to “follow their interest, think about how Project Play could develop their career or other areas of our work they would like to get involved in.”

Days of play

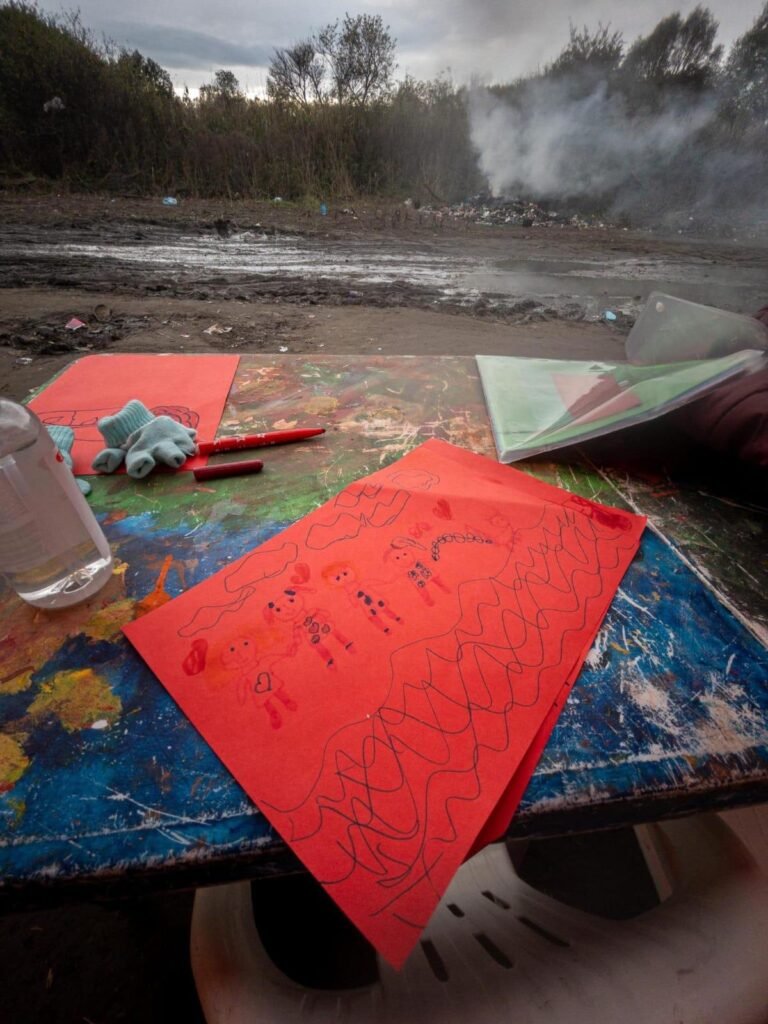

A typical day begins with waking up in the volunteer house, where up to 10 volunteers live at a time. The team heads into Calais to the warehouse/office they share with other organizations. Here, Project Play prepares for a session with the children. After a good meal, volunteers load up the van and spend the afternoons in session with the kids.

Gathering in a circle, a session begins with games and songs, often a favorite among the children. As Skyes shares, “It brings everyone together and is a great opportunity to be really silly!” This is a chance to build friendships and learn activities the children can do even when Project Play volunteers are not present. “Often we turn up to the session to hear the children leading their own circle time and singing the songs we sing together.”

After circle time, the main activity begins. According to Sykes, “this is planned according to the group considering their likes, ages and any additional needs — think sport, craft, drama and art.” A brief scroll on Project Play’s Instagram page reveals the different activities and themes it offers the children, including making edible “wands” for a magic week to playing ‘pin the nose on the clown’ during a circus-themed session. “We want sessions to be memorable and for the children to know how much we value them and their experience with us.”

Finally, the session concludes with free play, an important time for the children to practice autonomy and choice, which they often lack in their current circumstances. “We work closely with the children on this one and always try to incorporate their requests,” Sykes reports. Once the session is over, the volunteers hold a time of debrief and reflection before heading home to rest and recharge for another day of play.

Bringing play to migrant children

Project Play takes its services to various locations, including “day centers, safe houses and out in the informal living sites,” which are often “collections of tents in a rural area.” Finding the right space for a session can be challenging. Sykes admits, “Recently, there have been increased police evictions alongside worsening hostility towards organizations; we are now denied a space to carry out sessions and risk being fined.” Nevertheless, the team persists and generally tries to set up an enclosed space for play just a small distance away from the migrant camps in order to minimize distractions and interruptions.

Project Play is also highly committed to anti-racism in its work. “We acknowledge that we must examine our biases and explore our motivators and dynamics.” Since the beginning, Sykes informs, Project Play has discussed counteracting racial biases and systemic issues possible in humanitarian work and volunteering.

As part of its anti-racist practice, Project Play critically considers the ethnic and racial background of its volunteers during recruitment. Sykes notes, “We actively seek to recruit varied volunteers who can help diversify our view and approach.” Recognizing anti-racism is an ongoing process, the team members engage in educating themselves and drawing on available resources to improve their work continually.

Making an impact

Project Play is unique in its specialized focus on children. As Skyes describes, it is “the only service in the area targeting younger children.” Measuring the impact of Project Play through statistical reports and quantitative research is especially challenging considering the extreme vulnerability of migrant children. Still, the difference Project Play makes in the lives of displaced children in Calais and Dunkirk is tangible enough to touch.

Every Project Play volunteer leaves with a success story. The impact is visible in the smiles and giggles of the young participants, finding joy amid difficult circumstances. Shy children who are initially hesitant find confidence as they play. They make noticeable progress in regulating their emotions, working with others, and learning about themselves.

Countless children have enjoyed memorable experiences due to Project Play’s sessions, which Skyes credits as the most rewarding part of their work. Knowing that displaced youth can still make positive memories amid unfavorable conditions drives the passion behind Project Play.

Notably, Sykes asserts that the work of Project Play does not fully meet the needs of displaced children. “Our service is not enough — all children should have access to formal education in a warm, dry building. But, as long as the state refuses to meet this right, we hope to continue to spread some joy.”

The future of Project Play

The team remains committed to growing awareness of the situation at the UK/French border and providing even better services to migrant children and their families. “We want the British and French states to provide safe routes for asylum and ensure that all children are provided with a quality education. This is a right,” Sykes passionately resolves. Therefore, “we want to grow our advocacy capacity to better champion the amazing children we work with and push for change.”

The dream for Project Play? “Project Play doesn’t want to have to exist,” Sykes declares. Until then, Project Play continues its mission to ensure displaced children can do what they are meant to do: play.

Congratulations to Project Play for its efforts in providing enrichment to displaced children through play. Project Play was recognized with the Brighter Tomorrow Award on the 22nd of February 2024. On behalf of our Brighter Tomorrow team, thank you for taking the time to be interviewed.

If you are interested in submitting a piece to Yuvoice, please visit our submissions page here.

Yuvoice uplifts diverse voices around the world. We focus on perspectives of real people living through history and how Planet Earth looks through their eyes. We never necessarily endorse, promote, or agree with the pieces we publish. We want to showcase viewpoints of all types. Please check out our Statement of Global Progress for further information on our stance. And if you’ve enjoyed this piece, please drop a comment and support the author!

Laura Rodríguez-Davis

Laura Rodríguez-Davis is a writer and actor based in Belfast, Northern Ireland where she lives with her husband and dog. She recently completed an M.Phil in Conflict Resolution and Reconciliation at Trinity College Dublin. Originally from Florida, Laura is Puerto Rican and loves feeling more connected to the global community by living abroad. She enjoys dancing, reading, and comedy.